My ultimate guide to public speaking

When I was around seven years old, my mum offered me an opportunity: “you can have an ice cream if you go and buy it yourself”. But I was too scared to ask.

A few months ago I spoke at a conference in Korea in front of 300 senior energy industry professionals from around the world. I didn’t have a script, I was horribly jet-lagged and I had dislocated my left knee the day before (really).

And the result? The talk went well and I enjoyed myself.

I think public speaking is one of the most important skills that anyone can develop. It’s a superpower, a professional and personal cheat code, that can raise your profile, create luck, help you learn and just generally make you an all-round more competent human.

In this article I share the strategies I’ve learned on how to do it well – from the perspective of someone who would once have done absolutely anything to avoid it.

Now, I am no TED speaker. I still get nervous, I tend to talk too fast and I trip over my words sometimes. That’s okay, we’re all on a journey here. I hope that being an intermediate-level public speaker makes my experience more accessible.

And if you’re someone who is currently terrified of public speaking then have no fear. All of this is within your reach. My first manager advised me to take every opportunity to speak that presented itself. I promise that the fear you feel now will go away. Just keep trying and use the system here to help you.

Public speaking is a superpower

The best thing about public speaking is that most people are terrified of it. That gives a huge competitive advantage to anyone who chooses not to avoid it, since more of the benefits accrue to a smaller set of people willing to play the game. It’s a cheat code, just like writing online.

Why? Just look at the benefits.

Raise your profile

Let’s get this out of the way. As icky as it can seem, in modern life there’s nothing inherently vain or narcissistic about wanting to raise your profile, and nothing says “I’m worth your attention” like being on stage.

It also gives you credibility. As far as the audience is concerned, the fact that you’re there at all means someone thought you should be. You’ve already been through some form of quality control and deemed worthy.

Really understand your material

One of the best ways to learn anything is to practice active recall, where you review some material, hide it, and then see what you can remember. Preparing and giving a talk – just like writing an article – is the same process, but on a larger, more emotionally charged scale.

There’s real value in being forced to structure your thoughts into a coherent narrative. Compelling stories make a talk more interesting, more memorable and have a bigger impact on the audience. That same sense-making process is going on inside you as you prepare your talk.

Build transferable skills

Public speaking is not a single skill, but a diverse array of skills that are highly transferable between jobs and areas of life. As an arena to practice and hone these skills, speaking in public is unrivalled. To give a good talk, you need to:

- have and refine valuable ideas that are worth talking about

- organise these ideas into a coherent and interesting narrative

- understand the importance of pace and timing

- create visually appealing materials that help others understand your ideas

- speak in an engaging way to keep the audience’s attention

- build your confidence and learn to overcome your fear of being seen

Create your own serendipity

Events are a very different experience when you’re a speaker. As an attendee you have to make an effort to ’network’, but being a speaker means people make efforts to find you. This gives you access to higher profile attendees and other speakers at the event.

This effect continues once the event is finished. You’re more likely to get people contacting you with more opportunities, and the more events you do, the more this happens. The first time I spoke at a conference (in Denver) the invitation made its way to me through my employer. The second time (in San Francisco) I was invited to speak on almost exactly the same topic, except the invitation came directly to me as a result of my talk in Denver.

Plus, because work paid for it and I took a week off, I got to explore SF for cheap and, by even more luck, I even managed to catch my favourite band (Above & Beyond) who just happened to be playing there the day after my talk. Serendipity in action.

An emotionally resonant public speaking system

This all sounds good in theory, but it’s scary, right? However much we tell ourselves that it’s something we should do, the thought of speaking in front of an audience – especially a large one – can put us off. I remember having to give a talk at a company away day where I was so nervous I had to put down my notes because the paper was shaking visibly.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Over the years I’ve come up with a system that I use whenever I have to speak in public. This system works with the natural cadence and tendencies of my emotions, rather than against them. Let’s take a look.

Follow the steps

You find out that you’re giving a talk at some point in the future. Now what?

This is a scary moment! It’s easy to become overwhelmed and put off thinking about it, but be strong! Like any other project there’s a step by step process you can follow with different goals to achieve and skills to practice.

I break this down based on my state of mind with respect to the talk – how my body responds when I think about it. I’ve identified seven distinct phases:

- Long before the talk (weeks and months)

- Soon before the talk (hours and days)

- Immediately before the talk (seconds and minutes)

- During the talk

- Immediately after the talk (seconds and minutes)

- Soon after the talk (hours and days)

- Long after the talk (weeks and months)

So with that frame introduced, let’s dive in.

Long before the talk (weeks and months)

When you first say yes to giving a talk in the distant future, you may feel a wave of anxiety, but it passes quickly. At this point, the talk is far enough away that it probably won’t trigger a sustained emotional response, so you feel pretty calm. This low-fear state lasts a while and is the ideal opportunity to think and reflect.

It’s also a great time to promote yourself. You know those people who post things like “It’s a privilege to have been invited to speak at x on the topic of y – who will I see there?” on LinkedIn? You don’t need to be that, but some form of self-promotion will create more serendipity for you down the line. Sharing the fact that you’re giving a talk is also a great way to turn up your fear dials, which will help you grow.

Since this phase generally feels pretty safe, there’s a high risk of procrastination. If you do find yourself putting off starting then it can be helpful to imagine it’s the day of the event – just to give you a little kick of adrenaline. Just don’t work yourself up so much that the anxiety puts you off even more.

Instead, just follow these steps to create an interesting, engaging and polished talk that you’ll enjoy giving.

Consider your audience. Some number of people will be giving you their attention. What are they like? What do they care about? How could you surprise them? Just bring them to mind and let the idea that you’ll be connecting with living, breathing humans float in your mind.

Gather your ideas. It’s possible that all you have to work with right now is the title of your talk, so spend some time getting ideas out of your head and your reference systems and onto paper. How are you going to fill ten, twenty, or thirty minutes of content? This is a time for volume, not for quality. Get it all out.

Build a compelling story. Once you have all your ideas on a page, just look at them. Maybe go for a long walk, let your diffuse mode play around, then see if you can weave what you have into a story. It doesn’t need to be perfect and it’s fine for there to be holes. The aim is to get a sense for the shape of your talk.

Nail the transitions between ideas. One of the most valuable things to focus on is how you’ll move elegantly from idea to idea. You might know this topic well, so you’re likely to assume, even unconsciously, that your audience will be able to follow you easily. This is probably not the case. Even if you’re presenting to an expert audience, your particular framing will be unique, so you’ll need to hold their hand a little.

Test your story on people. Once you have your story, practice it on real people. It doesn’t need to be anything formal, just talk them through the key points. You’ll find out very quickly which parts you don’t understand yet and you’ll see from their reactions and questions where they get lost. Do this as many times as you can.

To take this to the next level, you can even just test idea fragments. You can have conversations around a single idea, you can write a short essay about one of the key arguments, or you can even tweet your ideas in different ways to see what resonates the most with people. This kind of thing can give you much faster feedback in a much more accessible way.

Cut what you don’t need. You’ve iterated a few times and you have an interesting story that others can follow easily. Now is the time to whittle it down to the core ideas that you really want your audience to remember and talk about later. Which parts of your story are gold and which are just filler? Kill the filler.

Design your presentation. It’s rare these days for a talk to come without slides of some kind. You’ll be tempted to start the whole exercise by opening PowerPoint (other software also available), but it’s really helpful to already know what you want to say before you start fiddling with your slides.

There are lots of approaches to making slides, but the one I recommend now is to go heavy on images and light on words. Aim to read very little off your slides. Instead, your slides should serve two purposes: to add greater resolution so that your audience feels more immersed in your story and to remind you of what your key points are in case you get nervous.

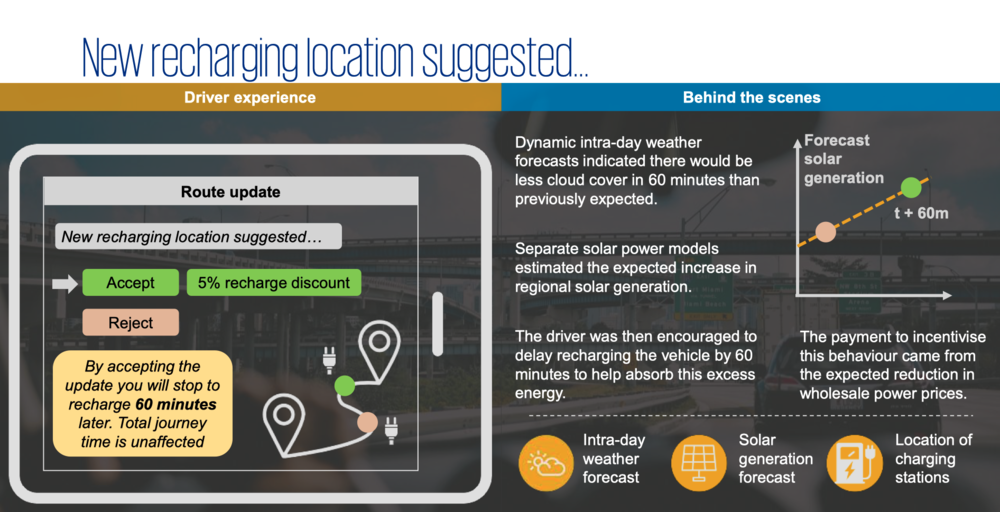

I used this approach for my talk in Korea, where the slides I made were essentially an exercise in design fiction. While I talked through the way an electric car driver might change where, when or how they recharged their car based on updates from their navigation system, my slides showed graphical mock-ups of what that system might look like.

By doing this, I made my audience a part of the story. First they took on the perspective of the electric car driver (left), then the perspective of the electricity network operator (right).

Test again. By this point you have prepared a full presentation, congratulations! Now it’s time to see if it all hangs together by – you guessed it – walking through it with someone in full.

I know, it seems tedious to do this again. But, honestly, it’s the only way to find out if something doesn’t work, particularly now that you have slides. And each run through you do will give you more confidence that you have strong material and that you know it well.

Learn your story thoroughly. You know that your presentation works. Now you want to make it as automatic as possible. I don’t mean in the sense that you’ll talk like a robot, but that you’ll know it so well that your mental resources will be freed up for other things, like smiling, connecting with your audience, and even cracking a joke or two. Remember, the more you rehearse, the less rehearsed you’ll seem. Practice, practice, practice.

Close to the talk (hours and days)

Not long to go now and you’re probably shifting modes from rational to emotional. Notice the shifts in your body as the big day approaches, because it’s important to change how you treat yourself from now on. I usually feel a combination of anxiety and excitement, two emotions that feel almost exactly the same in my body except for the way I judge it.

It was easy to be tough on yourself while your emotions were calm, but now you need to be more and more kind towards yourself.

Practice, but gently. It’s still a good idea to keep running through your talk in your mind, but do it softly. Ponder it in the shower, during your commute or as you get changed for bed. Keep it fresh in your mind, but don’t stress. You should be beyond learning it by this stage.

Visit the room. If you can, say if you’re speaking at a conference, go and see the room you’ll be speaking in. It’s a good idea to make it seem a little bit familiar so that it’s less of a surprise when you’re the one presenting in it. This is particularly valuable if it’s a big or imposing room, which is more likely to shock you if you’re not mentally prepared for it.

I’m glad I did this in Korea, which was by far the biggest and highest production event I’ve ever spoken at, and I would not have wanted to walk into this hall to see this stage for the first time just before giving my presentation. I even found out that I would be simultaneously translated into Korean, which meant I slowed down and added pauses to let the translators keep up.

Stop preparing. I find this absolutely crucial for managing my nerves before a talk and allowing myself to enjoy it. There comes a point where I just have to be done getting ready.

Let’s say it’s the morning of the talk. You might take a quick flick through your notes, but at this point your goal is just to relax and enjoy yourself. Let yourself off the hook and trust the work that you’ve put in up to this point.

Immediately before the talk (seconds and minutes)

I’ve done enough public speaking now to know how this ride goes, emotionally. I walk into the room and get a wave of, “woaah, this is real now”. Then I sit where I’m meant to sit, watch the other speakers and wait, until…the speaker before me is done, leaves the stage, and I’m introduced. It’s time to stand up, walk up on stage and go.

There’s an incredible change in perception when that transition happens, when the talk shifts from theoretical future event to holy crap I’m standing on stage holding a microphone. It’s an intense experience, which is why I have only one tip here.

Manage yourself, kindly. Recognise that you’re in a situation that is as scary as it is thrilling. Everyone – and I mean everyone – is emotionally turbulent at this stage and that’s fine. As you sit there waiting for your name to be called, be still, be quiet and pay attention to what’s going on inside your mind and body. Are you being kind to yourself? Could you breathe a little more slowly and deeply? Could you remind yourself that, not only are you in no actual danger, but that you wanted to be here?

At this point in Korea I was saying nice things to myself, intentionally slowing my breathing and reminding myself to let go and have fun. I have found my Zen practice to be really helpful here.

During the talk

One of the most wonderful things I’ve learned from saying yes to lots of speaking opportunities is that anxiety and fear peak immediately before giving a talk. Once I’m actually on stage and looking out at the audience, my anxiety levels drop by at least an order of magnitude and what’s left is feelings of exhilaration and playfulness. Here’s what I recommend doing with those feelings.

Have fun. It took me a long time to learn this, but public speaking can be seriously fun. It doesn’t have to be something to get through as quickly as possible. It can be something you can sink into and enjoy deeply. And if your current perspective won’t let you believe that’s true just yet, what would it take to change it?

Ignore your mistakes. Unless you’re a world expert, it’s almost inevitable that you’ll stumble at some point. You’ll mumble something, you may accidentally forget which slide is coming up next or you’ll say something in the wrong order. That’s all totally fine. Just notice the mistake, pause, correct yourself, and carry on. Audiences are far more forgiving than it may feel when they’re watching you.

Connect with your audience. It’s so easy to stay in your own little bubble on stage and forget that the audience is there. This might even be a defence mechanism, but resist! The more you can project yourself out into the room, the more engaged your audience will be and the more you’ll enjoy yourself.

Make and hold eye contact with lots of different individuals. Expand your spatial awareness out to the size and shape of the room, the way a great theatre actor would. At the very least, don’t just look at slides, your notes, or your shoes.

I always start by taking a couple of seconds to just stand there and look out at the audience. There’s no need to start talking immediately, and this moment gives me the space and time I need to connect.

Avoid ‘public speaking mode’. Beginner singers often get told to sing using their speaking voice, rather than going into what they think a singing voice is. The speaking voice is much more powerful, natural and totally appropriate for high quality singing. The same is true for public speaking.

It’s a common habit when giving a talk to go into a special mode. It’s one thing to speak more clearly and passionately, but it’s quite another to act like you’re someone else. I’ve found that the most natural way to give a talk is to do it conversationally, in exactly the same way as I would chat with someone before or after I go up on stage.

If it feels like you’re putting on some kind of ‘public speaking costume’ as you walk onto the stage then pay attention to this habit and see if you really need it.

Soon after the talk (minutes and hours)

From the moment you say “thank you” and the audience applaud, your entire psychological and physiological states change. This is another wonderfully physical change as all that adrenaline lets go. Here’s how to make the most of it.

Enjoy the moment. I always take a moment to offer myself some hearty congratulations – you did it! All that preparation paid off and any anxiety associated with the talk can now dissolve. Ride the wave of dopamine for a while, because you’ve earned it.

Talk to people. You may find an inclination to rush off after your talk, but try to hang around near the stage for at least a couple of minutes before you do and see what happens. It’s usual for at least a couple of people to come over, introduce themselves and ask a couple of interesting follow up questions.

What’s crazy is that these can often be quite senior people, who you would have had no chance of meeting if you’d been trying to ‘network’ with them. Remember that you’re the expert on that topic right now, so enjoy the chat.

Avoid intense self-evaluation. I’ve noticed a tendency in myself to immediately start critiquing my performance. “That was terrible, you really fouled up that part, you spoke too fast, how could you forget that important point?” And so on.

While it’s useful to be aware of how the talk went, I tend to put a moratorium on self-evaluation until at least a few hours later or the next morning. If my body and mind are still pumped up then I’m liable to get an inaccurate perspective on my performance one way or the other.

The only exception I make to this is some kind of non-judgemental journalling of the event. This is where the only things I’m allowed to write down are factual, objective observations – things a video camera would have seen. So I may write down “I forgot to mention the role of rapid electric vehicle chargers” rather than allow my mind to spiral into “I’m such an idiot for forgetting to mention the role of rapid electric vehicle chargers.” This can be useful later as a prompt for what happened.

Don’t plan difficult activities. While it doesn’t happen every time, I often find myself absolutely exhausted after giving a big talk. I always try to avoid making big plans that need me to be switched on for the couple of hours after the talk, though if I do end up having energy then I’m happy to use it.

In Korea I was horribly jet-lagged and had to caffeinate myself to survive the talk (which I don’t recommend). I was hoping to crash afterwards, but then found out I had to give an interview for my host organisation’s in-house TV channel. Let’s just say this was not ideal timing and I don’t remember much of it, which is probably a good thing.

Long after the talk (days and weeks)

You’ve been back home for a couple of days and everything is calm again. You might even be thinking ahead to another talk you have in the diary. The cycle is complete.

But if you’re interested in continuous improvement then now is the time. It needn’t take a lot of effort, so here are some final tips to squeeze all the remaining value out of your experience.

Reflect on your performance. Now that it’s easier to be dispassionate, you can evaluate yourself critically. What went well? What sucked? What areas would you like to work on for next time? I’m working on being more ‘natural’ on stage, more at ease, so I pay particular attention to triggers that cause me to speak in a more wooden or awkward way.

Consider why you’ll accept next time. I care about growing my public speaking skills, so I always want to be making things just a little harder for myself each time. That doesn’t just mean bigger audiences or longer talks, but exploring a whole range of different aspects of public speaking that I still find challenging. I find the idea of playing with my fear dials very helpful here.

For example, while I’ve done big, well-prepared conference talks, I’m still quite scared of speaking in front of smaller, more intimate discussion groups. I suppose it’s because the audience feels closer and I can feel their attention more keenly. To me it feels harder to hide in front of a small group than in front of a larger one.

Since accepting public speaking opportunities can be a massive time sink, I find it valuable to consider what skills I want to work on so that I can focus on the opportunities that let me practice those skills. I’ve done a few big conference talks now and want to practice the more casual style for a while.

Promote yourself again and share something of value. This is your last charge to prime that serendipity engine. Do you have any photos from the event? Any great insights or lessons that you learned? Don’t be afraid to share them publicly again. Who knows, they might one day turn into a 4000+ word essay on public speaking.

Looking ahead

I want to wrap up by reflecting on that nervous child I used to be, the one who gave up an ice cream rather than go and ask for it. He was too scared to use his voice and be seen. I’ve done all this for him.

For a long time I believed that public speaking was simply impossible for me. I thought my body just wouldn’t let me do it. After a few occasions where my notes would shake visibly in front of a small group, I avoided giving talks for a long time. I was the guy who would keep his eyes down in team meetings, who would never volunteer to ‘report back to the group’.

I hated the fact that I was so constrained and I hated myself for allowing it to happen. That’s why I’m so proud to be where I am now. I looked at my fear and decided to start walking towards it. Turns out that the closer I got, the more it dissolved. If any of that sounds familiar then believe me when I say that you can do it, because If I can then you certainly can too.

I knew I had beaten this thing when I was asked to speak at a “fireside chat” at the Canadian High Commission here in London with less than a week’s notice. I said yes without any hesitation, because I knew it would be fine. Now I’m excited for the future, with one less fear holding me back.